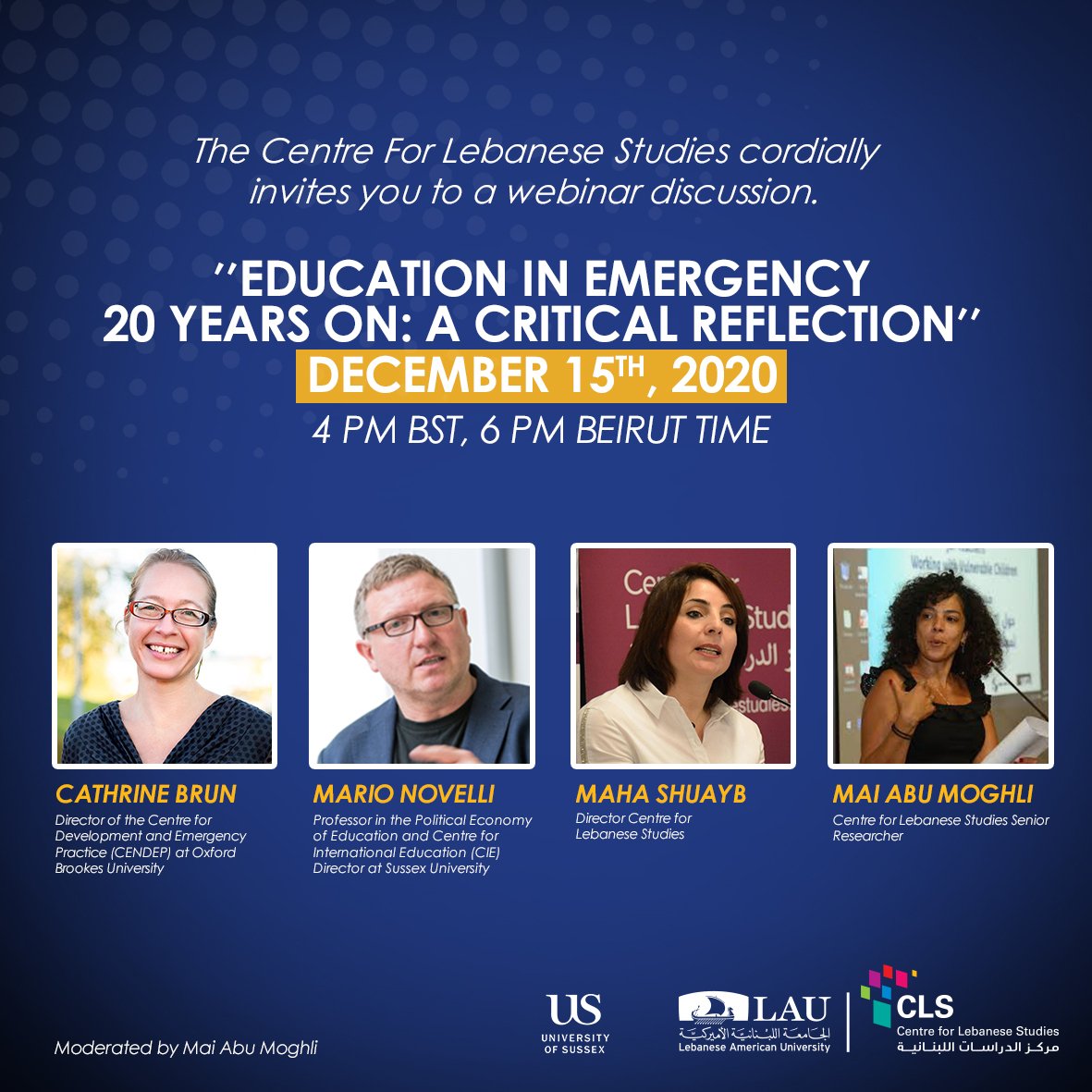

Education in Emergency 20 Years On: A Critical Reflection

Time: December 15th, 2020 4 PM BST, 6 PM EEST

Location: Online Event

Join Centre for Lebanese Studies Senior Researcher Mai Abu Moghli, as she moderates the discussion with Director of the Centre for Development and Emergency Practice (CENDEP) at Oxford Brookes University Cathrine Brun, Professor in the Political Economy of Education and Centre for International Education (CIE) Director at Sussex University Mario Novelli, and Centre for Lebanese Studies Director Maha Shuayb.

They will reflect on 20 Years of INEE. What was achieved? Where did it fail? And who to prioritize in education and financing of education in emergencies?

Mao Abu Moghli

Speakers critically examined what has become an industry of education in countries affected by crises rather than teaching and learning, knowledge production or service provision. They also discussed the fixation on numbers, access to schooling rather than the concept of education, political economy, funding in the emergency education, ethics of care, and knowledge production.

Mario Novelli

Raising awareness about the role of education in emergency, mobilizing resources, systemization, improvement in coordination and the efforts of INEE and global educational clusters are successes of twenty years of education in emergency. A widening research network, powerful debates, dedicated journals, and a generation of doctoral students, committed practitioners, and advocates have also been established. However, the field continues to be shaped by broader international politics which undermine and distort education in emergency. It needs to be understood within it geographical, historical, political, economic, and ideological contexts. It is a ‘field caught between white saviors and Machiavellian characters.’ Funding for education is dominated by power nations and reflects their priorities. It remains at the back of funding priorities and is very nation state centric.

Maha Shuayb

Education of refugees happen in a-politicized and protracted contexts for conflicts that span over decades. Negotiations and compromises often happen between donors states and host nation states to fulfil both of their agendas often at the expense of refugees. Even with less than 4% of ‘refugee’ students making it to secondary schools in Lebanon, their inclusion in nation state is still not problematized. Knowledge production on the topic of refugee education remains uncritical. It did little to question the purpose of education for refugee children and has contributed to the reification of refugees as being ‘unique’. Most of INEE’s research rarely looks at the case of refuges in the Global North, as if research is reduced to scholars in the Global North talking about refugees in the global south. It didn’t draw on other literature in education concerned with the education of marginalized children. Finally, it maintained the unequal power dynamics in the knowledge production cycle between scholars in the global north and those in the global south. The research industry in this field needs to be reconsidered, as scholars in the global South we are often reduced to field collectors fitting under the localization agenda.

Cathrine Brun

Education in emergencies has been established at the core of humanitarian agenda creating tensions particularly in long term displacement. Progress over the last two decades has stood still raising concern about making education such a vital part of the humanitarian agenda. Humanitarianism and education operate in different temporal logics making it challenging to bring together. The ethical foundation of humanitarianism contributes to a decontextualized and a-politicized approach to education, it is grounded in neutrality but remains highly political. Finally, the need to move from humanitarian to a developmental approach in education includes a more inclusive approach and an acceptance of the refugee presence. These are measures with significant consequences leaving refugees’ children to endure both forced integration into their host country’s curriculum and face little prospects of future social, economic, or cultural integration. To achieve any progress a shift in logic to ethics care factoring the refugees into the equation and securing their future may be a good start.