This Op-ed is part of Towards an Inclusive Education for Refugees: A Comparative Longitudinal Study funded by the Spencer Foundation

During an interview conducted by the head of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Refugees Filippo Grandi on education in exile on February 16, 202, he praised the achievement in the field of refugee education around the world, as enrollment rates in primary education have risen to 77% over the last decade. He also pointed to the difficulties that still exist, as the percentage of refugee education in secondary education decreases, which does not exceed 30% and 3% in higher education. Filippo did not address the reasons for the non-completion of education for refugee and refugee children and the obstacles that lead to their dropping out of school.

The realization that most refugee crises are protracted and long-term responses must be introduced has settled in over the last decade (Brun and Shuayb 2020a). This realization resulted in a shift from humanitarian responses to a developmental one, and including education in humanitarian response is one manifestation of such a shift. While this step is noted progress in the humanitarian discourse (Brun and Shuayb 2020b), there is a need for evidence-based research to adequate education provisions.

In this Op-ed, we examine the humanitarian education response to Lebanon’s Syrian refugee crisis and discuss its effectiveness. We draw on Wave 1 of our ongoing longitudinal comparative study conducted with seven graders in Lebanon, Turkey, and Australia, but we only report on Lebanon’s findings. Our survey covers 418 national and refugee students in 14 public schools offering morning and afternoon shifts across six governorates (Shuayb et al., 2020).

Education in Emergency and Humanitarian Responses: the Case of Lebanon

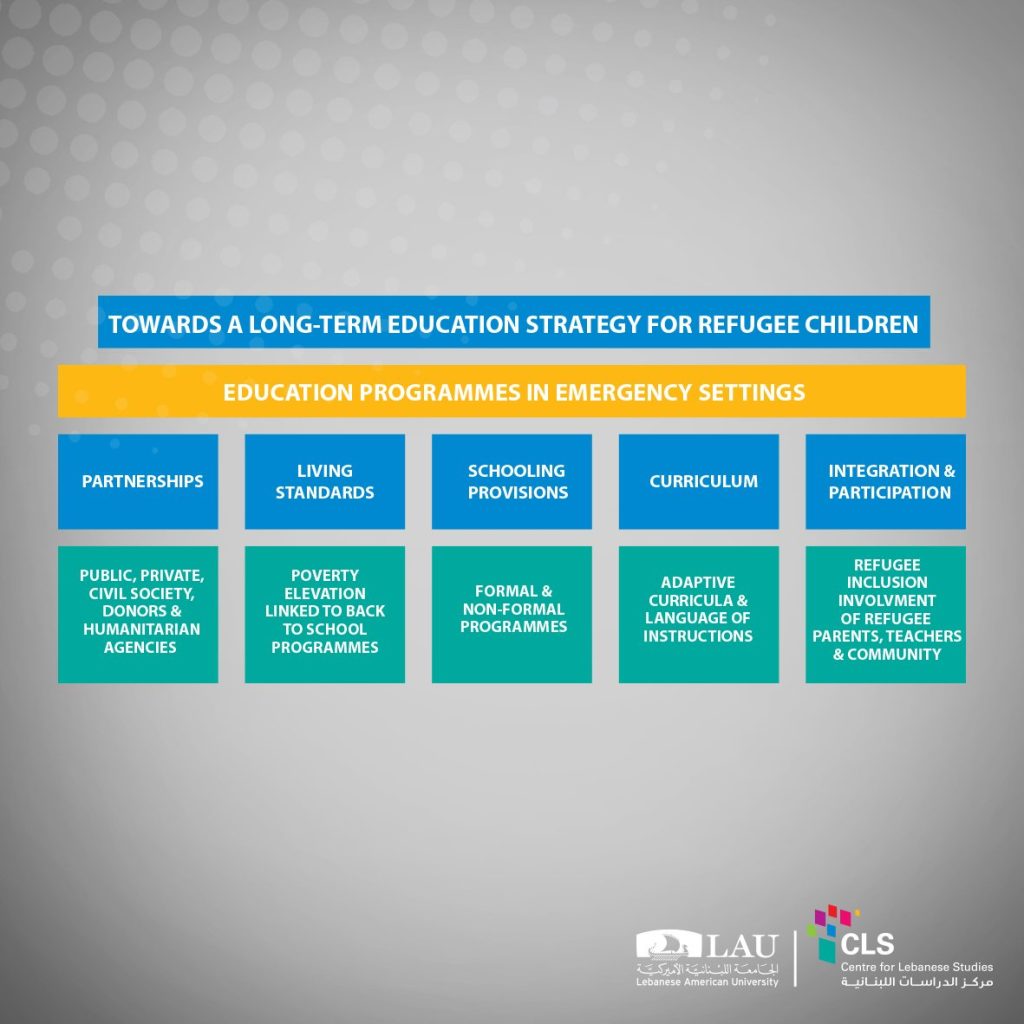

‘Education in humanitarian’ settings, commonly referred to as Education in Emergency (EIE), is the most widely used paradigm for thinking and planning education of refugee children living temporarily in a hosting state while awaiting repatriation (Brun and Shuayb, 2020b). Lebanon certainly fits this description where the government refers to all individuals from Syria as displaced people or visitors (LCRP, 2018). This humanitarian logic for dealing with refugees emphasizes short-term approaches and limits any long-term social, economic, or educational integration. Including education in the humanitarian response to the Syrian crisis in Lebanon, planning and implementing education policies for refugee children is coordinated between the Lebanese Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MEHE), donors, and UN agencies. Together they developed RACE I and II (RACE I 2014, RACE II, 2017), two educational strategies to absorb 500,000 school-age children in a public educational system that can only accommodate 200,000 nationals. The challenge is undoubtedly huge for any structure, let alone for a country like Lebanon, where the public education system is already struggling. The strategy designates public schools as the main route to Syrian refugees’ formal schooling. Second shifts were introduced and currently accommodate over 75 percent of enrolled Syrian children, with the remainder attending morning shifts. According to MEHE, the morning shift enrolment rates are too high for these agreed-upon regulations (PMU, 2019) and is currently taking steps to decrease these numbers and push more Syrian students to the afternoon shift. MEHE states that the cost of enrolling students in the morning shift adds a burden on the public system, as MEHE charges 300 USD per child in the morning shift compared to 600 USD in the afternoon (PMU, 2019). It is worth noting that Syrian families favor enrolling their children in the morning shifts because they naturally perceive the quality of schooling to be better. Some parents also choose not to send their children late in the day to avoid having them return home after nightfall. Furthermore, second-shift classrooms are exclusively staffed with Lebanese contractual teachers, some underqualified (LCRP, 2018). By limiting learning hours from 2:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m., leaving no room for adequate breaks, physical education, or art classes, children’s learning experience is also compromised (Brun and Shuayb, 2020a).

In addition to formal schooling, MEHE also enrolls Syrian refugees in vocational schools and offers accelerated learning programmes to support Syrian refugee dropouts’ re-enrollment. However, less than 10% attending these programmes end up enrolling in public schools. RACE I and II offer a limited view on secondary and higher education enrollment for Syrian refugee children.

Schooling Outcomes for Syrian Refugees after a Decade

According to the RACE II fact sheet (2019), a total of 206,061 Syrian refugee students (60 %) are enrolled in formal primary education distributed between morning (52,775) and afternoon (153,286) shifts and 4,903 in formal secondary education. According to the Programme Management Unit (PMU), about 4,000 non-Lebanese are enrolled in vocational education; however, it is unclear if they are only Syrians or include other nationalities.

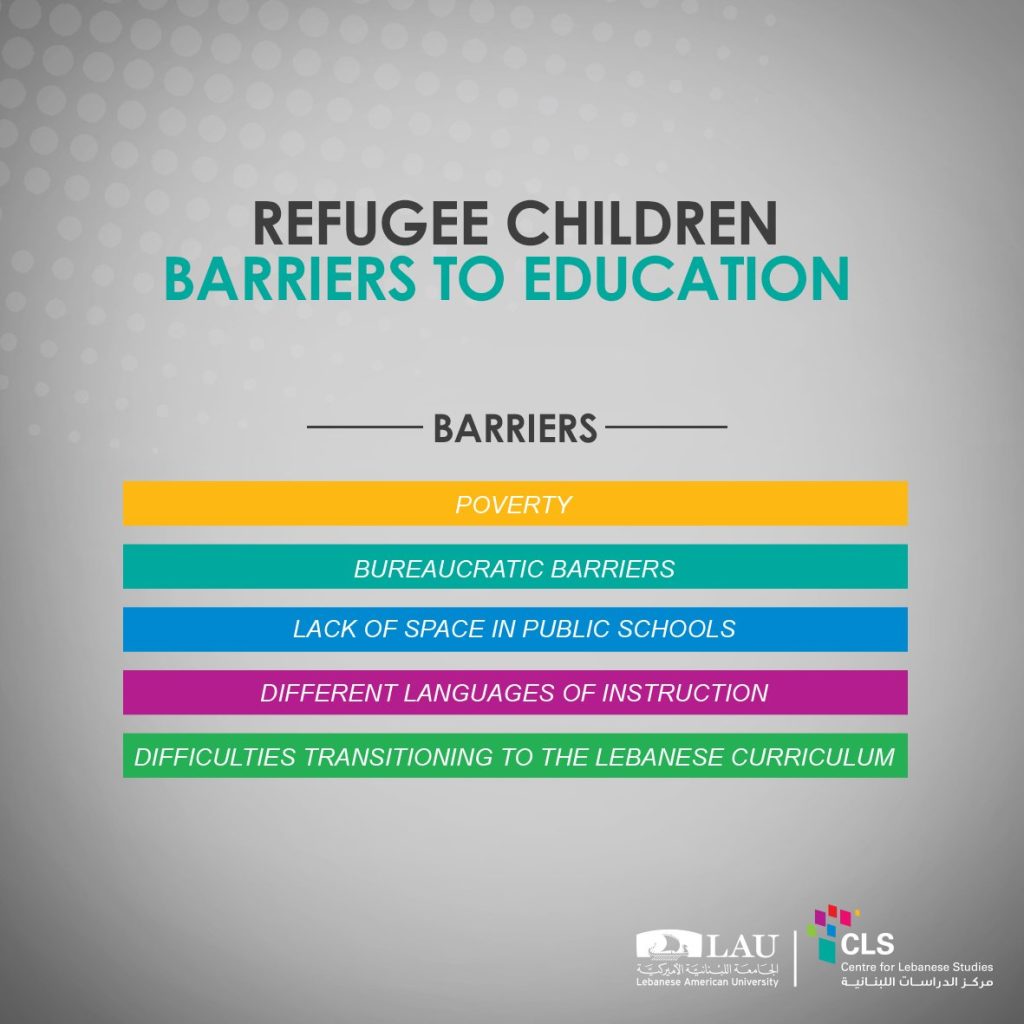

Despite an increase in enrollment rate, other PMU indicators give a different story. For instance, there is a steady decrease in retention rate as students progress in school. For example, less than 4% are enrolled at the secondary stage, and only 1% are in grade 9. A study by the Norwegian Refugee Council (2020) indicates that (i) 78% of out-of-school children could not register due to poverty, (ii) 62% were forced to drop because of financial reasons, and (iii) 52% have never been enrolled in either formal or non-formal schools.

To understand the experience of Syrian school-age refugees currently enrolled in public schools, we present our survey results.

Experience of Syrian and Lebanese Students in Morning and Afternoon School: Survey Result

The vast majority of surveyed (94%) reported liking coming to school but struggled with some school subjects.

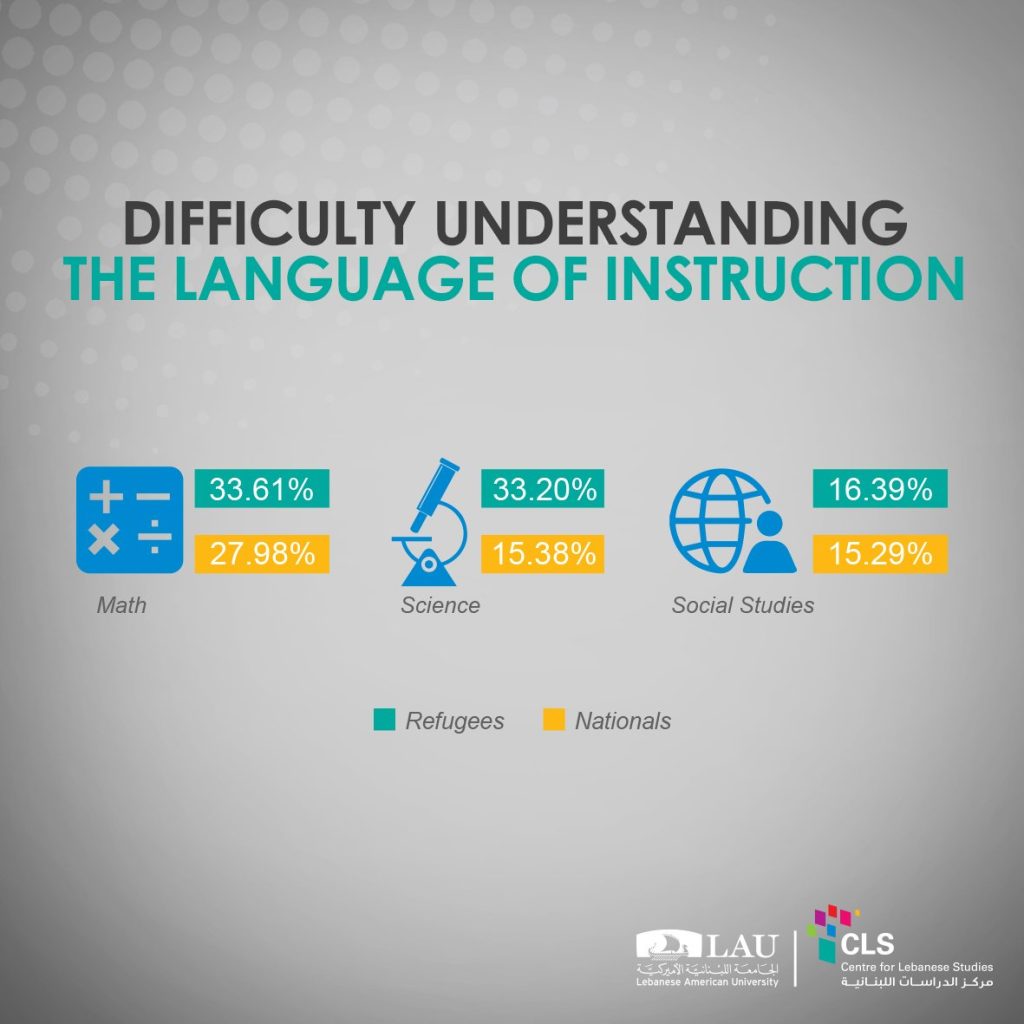

The percentage of refugee students who reported facing difficulty understanding the language of instructions for lessons taught in a foreign language is double that of those who reported facing difficulty understanding the language of instruction for subjects taught in their native language. One-third reported difficulty understanding math and sciences when taught in English or French, but only 16% said they had difficulty understanding classes taught in Arabic, such as social studies. The percentage of students facing difficulties because of the language of instruction was greater among refugees than nationals. The difference is most prominent in classes relying on a foreign language of instruction like science and lesser in subjects like math. The difference between nationals and refugees narrows down for subjects like social studies taught in Arabic for both.

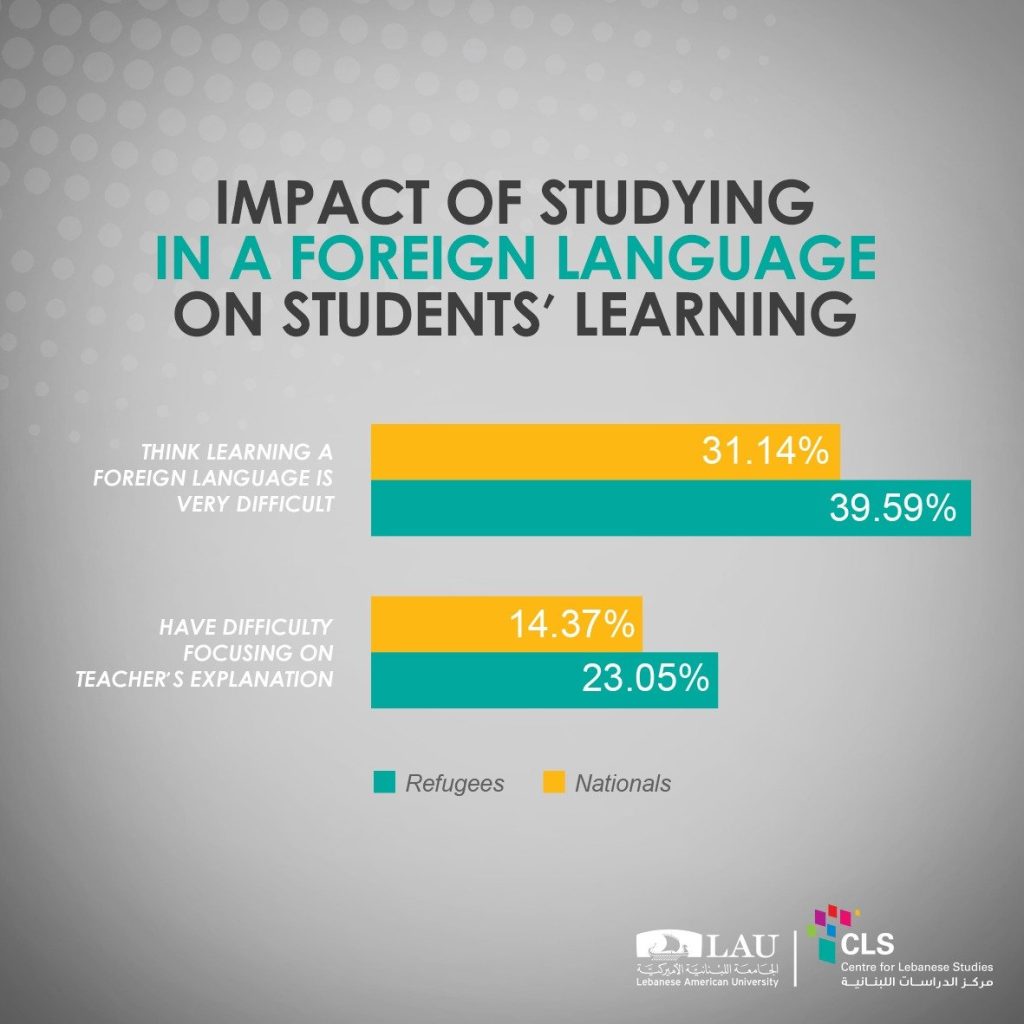

The study also shows that 40% of Syrian refugee students agree that learning English or French is tough compared to 31% of nationals. The language barrier can also act as a deterrent to the success of in-class practices, such as focusing on the teacher’s explanation, with a quarter of refugee students reporting difficulty focusing compared to only 14% of nationals.

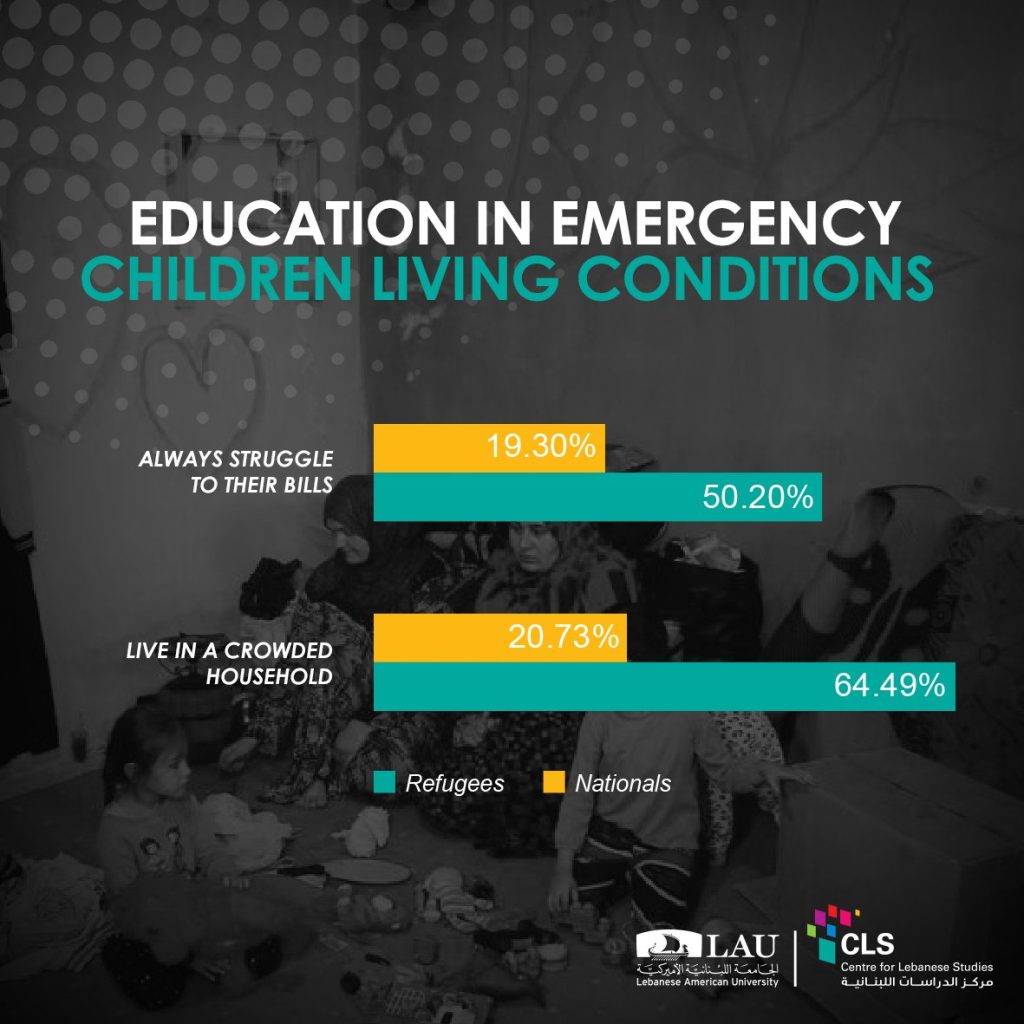

Poverty is a determining factor according to our survey, with 50 % of Syrian students reported struggling to pay their bills, and 70% reported living in crowded homes.

Half of the respondents (50%) moved houses several times, with the cost of dwelling reported as the most common reason

Conclusion

Putting education at the heart of the humanitarian response to the Syrian crisis in Lebanon meant that a structured programme and medium-term education strategies were put in place by the hosting government and UN agencies. While offering formal accredited schooling for refugees was proposed as a better alternative to non-formal education, low retention and progression rates prompt us to think that something is missing. Lebanon’s humanitarian education has no clear long-term objectives, mainly because refugees are denied their civic, social, and employment rights. Education with no prospects makes it a futile investment for many refugee families and their children already struggling financially, emotionally, and economically. Schooling must always have a long-term purpose and most importantly be linked to rights of participation in the workforce and society; otherwise, it remains at best, a literacy programme. Poverty constitutes the main barrier to education, and poverty elevation programmes must be part of any refugee education enrollment campaign envisaged. Public schools in Lebanon need to triple their current capacity to allow access to Syrian children, an almost impossible task at this time, prompting a dire need for partnerships between the public and private sectors, and civil society.

For further details about this study, refer to our “Towards an inclusive education: A comparative longitudinal study.”

References

Brun, C., & Shuayb, M. (2020a). Exceptional and futureless humanitarian education of syrian refugees in Lebanon: prospects for shifting the lens. Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees, 36(2), 20-30.

Brun, C. and Shuayb, M, (2020b) Education in Emergencies: five critical points for shifting the power”, https://lebanesestudies.com/education-in-emergencies-at-20-five-critical-points-for-shifting-the-power/

Shuayb, M., Chatila, S., Kelcy, J., Maadad, N., Zafer, A., Crul. M., & AboulHosn, A. (2020). Towards an inclusive education: A comparative longitudinal study. Centre for Lebanese Studies https://lebanesestudies.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Lebanon-Report.pdf

Norwegian Refugee Council. (2020). The obstacle course. Barriers to education for Syrian refugee children in Lebanon. https://www.nrc.no/resources/reports/the-obstacle-course-barriers-to-education-for-syrian-refugee-children-in-lebanon/

Plan, L. C. R. (2018). Plan 2017–2020. Government of Lebanon and the United Nations. https://reliefweb.int/report/lebanon/lebanon-crisis-response-plan-2017-2020-2018-update/

Project Management Unit (PMU). 2019. RACE 2 fact sheet March 2019. http://racepmulebanon.com/images/RACE-PMU-Fact-Sheet-September-2019.pdf